Before the Japanese pop culture staples made their way to the West, manga and anime were a constant.

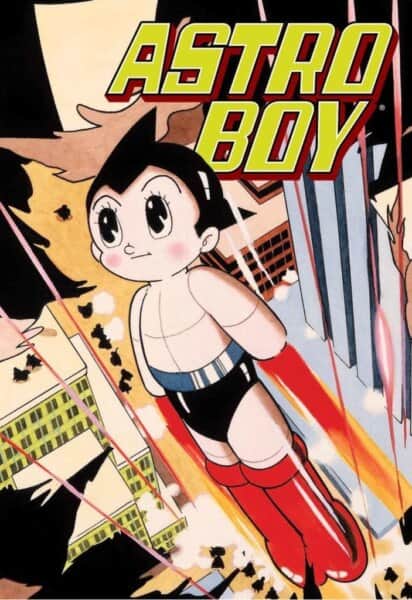

Although the Japanese name “manga” dates back to the late 18th century, it wasn’t until the 1960s, when the Japanese animation series Astro Boy was brought to the U.S., that this kind of comic started to acquire popularity here.

By 2007, the anime market had reached its all-time high in the United States, reaching a value of about $4.35 billion. But Astro Boy belongs to the modern anime, so for us to know how and when manga and anime started, let’s head back to 1798.

This is the history of manga and anime.

The Rise of Manga and Anime

The Japanese word for comics is manga. The definitive book Shiji no yukikai served as the inspiration for the phrase’s initial use in 1798.

The phrase cropped up again in 1814 as the title of Aikawa Minwa’s Manga Hyakujo and Hokusai Manga, which contained drawings by the artist Hokusai.

1917 saw the release of nearly twenty short animated films in Japan. Still, Dekobo Shingacho – Meian no Shippai (Dekobo’s New Picture Book – Failure of a Great Plan) is the first Japanese animated picture we are positive was commercially published.

The first World War was still happening, and animation was a fresh discovery. Oten Shimokawa, Junichi Kouchi, and Seitaro Kitayama, two manga artists, were enthralled by this novel genre.

These three guys, known as “the fathers of anime,” were hired by established film studios and produced a great product that first year while working with relatively tiny crews.

The movies they produced did not resemble the anime produced today. The runtimes were incredibly brief, typically under five minutes, and neither translucent cells nor colour were used. The lines were erased and redrawn on a board during the production of the early movies.

The somewhat less time-consuming method of employing paper cutouts—2D stop-motion animation—quickly surpassed this technique.

The movies were silent but surely accompanied by “benshi,” storytellers who stood by the screen and provided the audience with narration.

The movies of 1917 were produced for already-established movie studios. Kitayama quit his job at Nikkatsu in 1921 to start Kitayama Eiga Seisakujo, the first anime production firm.

Following in his father’s footsteps, Kouchi established his own animation company, Sumikazu, in 1923. Sadly, neither studio made it through the decade. Making money with anime is challenging.

However, people began to talk about the great quality of Japanese “manga films.” They started off with an uphill battle. Production of Anime for public relations and publicity campaigns by government organizations was one of the factors that assisted them in finding their niche.

When Tokyo and the surrounding area were devastated by the Great Kant Earthquake in 1923, domestic anime production was starting to establish a modest but strong basis. The anime business had to rebuild from scratch.

Modern manga emerged amid an explosion in Japan between 1945 and 1952 when the United States was the country’s occupier.

U.S. forces brought American cartoons and comics to Japan during the occupation, including Mickey Mouse, Betty Boop, and Bambi, encouraging Japanese cartoonists to create their own distinctive style.

Although Hakujaden was not the first anime to cross the Pacific, it stressed that international markets may be successful sources of additional income. Film enthusiasts have been shipping each other reels since the medium’s birth.

With its colourful figures and easily-replaced language, animation was especially easy to ship across the seas.

Anime was and still is frequently purposefully set in locations outside of Japan or otherwise downplays its national origin to make it more appealing to audiences and wallets outside, depending on the hoped-for market.

After the war, we start to see names that even casual anime viewers are now familiar with.

Toei, the Japanese company that acquired Japan Animation Films in 1956 to establish an animated division, is probably more familiar to you than Japan Animated Films, founded in 1948. In 1958, they distributed Hakujaden (The Tale of the White Serpent).

It had a 78-minute running time and was the first full-length, colour-animation movie. Three years later, in 1961, it would be released in America.

But remember Osamu Tezuka? After the Second World War, Osamu Tezuka, a young aspiring artist in Japan, started drawing cartoons and published his first book, Shin Takarajima (known in English as “New Treasure Island”).

Tezuka was an avid follower of Walt Disney’s early animations as a child. The unique style of Tezuka wowed many people. Tezuka was hailed as “the Father of Manga and Anime.” Still, it wasn’t until he published

Tetsuwan Atomu (Astro Boy) that he found fame. Tezuka started his own production firm in 1962 after becoming well-known. He established Mushi Productions, where he published Astro Boy, his finest work.

Many people recognized Tezuka’s unique style and approach, which was novel to the entire business, in Astro Boy. German and French films influenced his graphics and characters.

His stories would expand over hundreds of pages, and his characters would burst with life and emotion. By 1963, Astro Boy had premiered on NBC stations across the U.S. and had crossed international borders. It was still a hit with American viewers.

Tetsuwan Atomu’s cheap franchise fees, which were provided to the studio by Tezuka Osamu, the head of Mushi Production, meant that the business had to find a means to reduce production expenses significantly.

The number of drawings was brutally reduced, the number of lines in each image was reduced to a minimum, and more still photographs were used. They tried to shorten the tales and devised innovative techniques for imitating movement, from sound effects to conversation.

By licensing the Atom character to its corporate sponsor, confectioner Meiji Seika, who featured the character on a well-known chocolate brand, the company was able to offset its losses.

When the business continued to make a loss, Tezuka decided to invest his earnings from the sale of manga.

Later, additional artists like Akira Toriyama, Rumiko Takashi, Hayao Miyazaki, Isao Takahata, and many others arrived to share some of the attention.

Miyazaki, a Studio Ghibli employee, is one of the most well-known and esteemed animation creators working today.

Kiki’s Delivery Service, Heidi, Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, and his most recent masterwork Princess Mononoke are just a few of Miyazaki’s works.

The Golden Era of Anime

The 1980s, regarded as the “golden era” of anime, experienced an enormous boom in popularity and genres.

This was influenced by several things, including the invention of VHS and the ageing of Tetsuwan Atom-inspired young people who grew up and had nostalgia for their beloved shows.

Captain Tsubasa by Tsuchida Pro, a program about soccer (or football for non-American audiences), collaboration, and camaraderie, established the formula for sports anime in 1983.

It served as an inspiration for a generation of soccer players and manga creators. It established the benchmark for ever-cooler and more absurd anime sports techniques.

Kaze no Tani no Nausicaä (Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind) was the biggest story of 1984. Produced by Isao Takahata and directed and written by Hayao Miyazaki, it was the first film of the legendary Studio Ghibli.

However, 1984 witnessed another first if auteur-driven OAVs and enormously influential films and studios aren’t precisely your thing.

You can probably guess what industry jumped on board as soon as consumers discovered they could purchase anime and watch it in the privacy of their own homes without the censorship and media attention of T.V. and cinemas.

Lolita Anime was the first “hentai” (pornographic) release, while Cream Lemon from the same year is more well-known. Following after and profitably were more titles.

Toei animated the Dragon Ball series by Akira Toriyama in 1986.

The show proved tremendously popular. You undoubtedly watched Dragon Ball or its successor Dragon Ball Z as a child if you’ve appreciated any “shonen” (aimed at boys between the ages of 6 and 15) television series in the past 30 years that featured drawn-out battles and ever-increasing hero power-ups.

Sources for anime were growing. Manga, books, and original works of fiction were constant favourites. Still, video games and light novels would soon follow as profitable genres.

Additionally, a wider range of stories is now being adapted. Kaze to Ki no Uta, an OAV, was the first B.L. (boy’s love, commonly known as “yaoi” or “Yuri,” and featured gay relationships aimed towards women) anime. Small animation studio Office Next-One produced it in 1987.

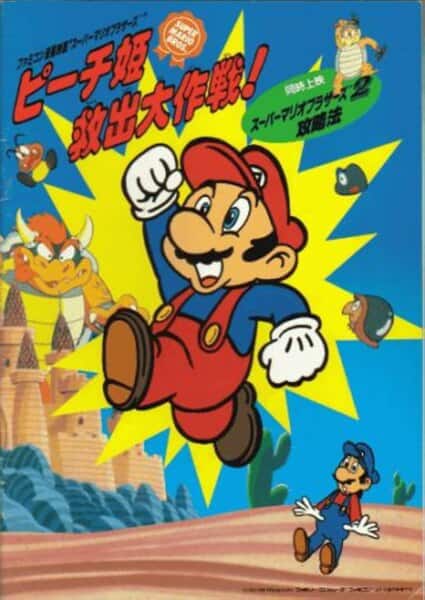

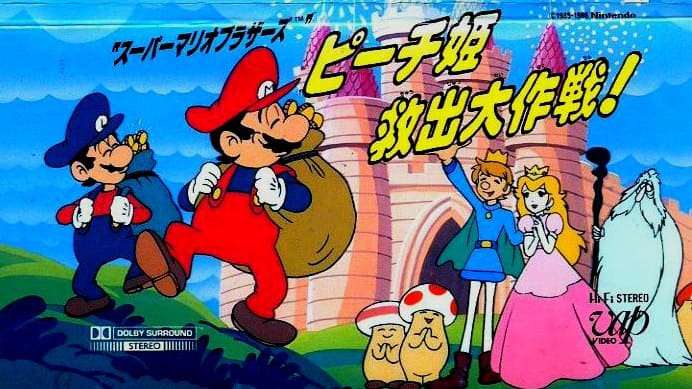

Super Mario Brothers: Peach-hime Kyuushutsu Daisakusen (Great Mission to Rescue Princess Peach), released in 1986, was the first video game-based anime, while Pokemon, released in 1997, marked a stunning and financially successful turning point for the genre.

Studios are still attempting to imitate its widespread success while airing. Of course, not all video games are marketed to children; in fact, adult-oriented visual novel games—especially, yeah, the pornographic ones—started to be mined for source material as well.

Sentimental Journey was the first to come out in 1998, and the genre took off in the 2000s.

Early in the new millennium, anime was once more thriving.

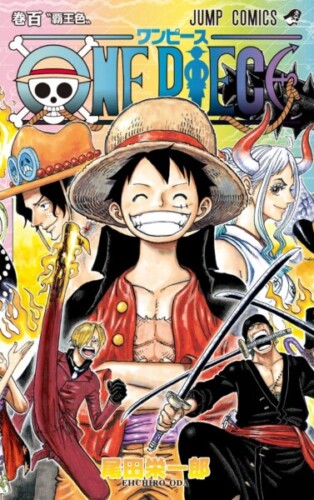

Numerous successes boosted the domestic and international markets. One Piece (1999), Naruto (2002), and Bleach (2004) were examples of long-running series that cross-promoted manga sales with movies, video games and merchandising.

Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi (Spirited Away), from Studio Ghibli, won the Best Animated Feature Oscar in 2002 due to the explosion in international licensing. In 2000, the first ONA (original net anime) was released.

Created by J.C. and Adapted from the four-panel manga series Azumanga Daioh, it was only four minutes long and told a brief tale.

The intention was to see whether there was enough desire to develop a series of episodes for the internet. Still, there was so much interest that it made a standard anime T.V. series instead.

Anime Today (2023 and beyond)

Anime is regarded as a dependable source of art and enjoyment on a global scale.

Disney’s creations influenced early Japanese animators; today, Western productions like Avatar: The Last Airbender and Samurai Jack are influenced by Japanese animation.

Studios keep adjusting to changes in storytelling techniques. Still on top of the list, Attack on Titan and One Piece are among the most-watched television programs.

Two distinct short anime series have been created specifically to be seen on mobile devices.

The industry has seen a lot of change. Although it is hard to predict where humanity will be in another century, we can make pretty good educated estimates by looking at the past.

Sazae-san will continue to operate, studios will grow and fall, budgets will increase and decrease, and animators will innovate with cutting-edge technology to make timeless stories—or whatever their sponsors will pay for in the interim.

Because those stories will be anchored in the rich heritage of anime, they will continue to attract admirers worldwide using Japanese narrative and animation skills passed from animator to animator.

The Japanese animation market is about to change. The truth is that many anime production businesses have financial difficulties and have essentially devolved into mere subcontractors for television networks.

The first of many problems that must be solved if the sector is to continue producing fresh talent for the future is the need to raise the status of these businesses.

–

Recommended Next:

How Anime Has Radically Evolved In The Past 60+ Years